Byzantine Mosaics

Empress Theodora and Her Court; Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. Image © Wikimedia Commons user Neuceu

Byzantine Mosaics

(ψηφιδωτόν, μουσαϊκόν), the most elaborate and expensive form of mural decoration (see Monumental Painting) employed by the Byz. With the toleration of Christianity in the 4th C. and the beginning of the construction of churches, the use of small cubes (tesserae) as an artistic medium was no longer limited to floor mosaics. It was deemed more appropriate for depictions of sacred personages and biblical events to be placed on the walls and ceilings of churches than on floors where they might be walked on. The gradual shift to mosaic for mural decoration made possible the use of a greater variety of more fragile materials for the tesserae; in addition to the multicolored stone and marble typical of floor mosaic, artists used brick or terra cotta, semiprecious gems, and opaque colored glass. Gold and silver tesserae were produced by sandwiching foil between layers of translucent glass. Tesserae varied much in size, the smallest being used for modeling faces and other important details. Often following preliminary, painted guidelines, the mosaicists impressed these tesserae into a setting bed, itself laid over previous plaster strata. While tesserae could be produced in a small local workshop, as at Masada in the early 5th C. (Y. Yadin, IEJ 15 [1965] 102), mosaic decoration on a large scale presupposes huge financial investment and industrial organization. The mosaic in the apse of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople required almost 2.5 million tesserae “smeared,” as Photios said, “with gold” (Cutler-Nesbitt, Arte 106). Depending on the size of the tesserae used, a mosaicist could cover up to four square meters per day (I. Logvin, Kiev's Hagia Sophia [Kiev 1971] 16).

In contrast to fresco technique, mosaic is an essentially additive medium, contributing materially to the dominance of line and contour. This inherent linearism could be overcome only by the use of microscopic cubes, such as are found in miniature mosaic icons of the 11th C. and later. Despite this limitation, mosaic was, at its best, a medium of great subtlety, involving hundreds of shades of color.

In late antiquity, wall mosaics were subordinate in extent to floor mosaics and were restricted to such surfaces as domes and the conches of apses until the 6th C. During the reign of Justinian I a new model was established at Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, paved in marble but with its upper surfaces sheathed with “the glitter of cut mosaic” (Paul Silentiarios—ed. Friedländer, Kunstbeschreib. 245.647). Mosaic was more widely used in this period than it was to be ever again; the finest 6th-C. examples survive at the monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai, Poreč, and Ravenna; others are found at Dyrrachion, Gaza, and at several sites on Cyprus. Mosaic was soon to become an important Byz. export. Thus in the early 8th C. the Arabs imported from Constantinople “40 loads of mosaic cubes” and a number of workmen for the decoration of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (H.A.R. Gibb, DOP 12 [1958] 225–29), while Pope John VII seems to have employed Byz. mosaicists for his oratory in St. Peter's, Rome (P. Nordhagen, ActaNorv 2 [1965] 121–66).

By the late 8th C., holy figures executed in mosaic were a common feature of sacred decoration: the author of the vita of Stephen the Younger complained that the images of birds and beasts set up by Iconoclasts in the Church of the Blachernai to replace a Gospel cycle left the building “altogether unadorned” (PG 100:1120C). The economic revival of the 9th and 10th C. saw the frequent use of mosaic in the churches and private chapels of Constantinople. It was also the model of luxury in palace decoration, attested for the Kainourgion at the Great Palace built by Basil I (TheophCont 332.14–335.7) and in the epic of Digenes Akritas.

Mosaic was the technique chosen for imperial portraits in Hagia Sophia for three centuries (9th–11th) and was favored in the 12th C. by Manuel I for scenes of history painting (Nik.Chon. 206.48–52). In emulation of the empress Helena, the same emperor may have sent mosaic cubes and even craftsmen such as Ephraim to Bethlehem for the Church of the Nativity. Clavijo describes mosaics (of the 12th or 13th C.?) in both the church and cloister of the Peribleptos monastery in Constantinople, as at St. George of Mangana. It is also known that large areas of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople were decorated by Eulalios in the 12th C. The 11th and 12th C. in general represent a high watermark in work in this medium. The decorations of Hosios Loukas, the Nea Mone on Chios, and Daphniwitness to the transport of artists and materials over great distances. In the early 11th C. smalt and mosaicists were sent to Kiev for the embellishment of St. Sophia (A. Poppe, JMedHist 7 [1981] 41–43), and local workmen were taught the craft. A similar importation probably prevailed during the protracted decoration of San Marco in Venice, and mosaicists figure among the other craftsmen brought from Constantinople in the 11th C. by Desiderius of Montecassino. The extent to which Byz. artists participated in the 12th-C. mosaic decoration of Palermo and Monrealeremains in question.

From the 13th C. onward mosaic was used only in the most lavish enterprises at Constantinople and, exceptionally, at Arta. While the mosaic of the Deesis in Hagia Sophia (late 13th C.) may have been an imperial commission, later programs, such as those at the Chora and Pammakaristos in Constantinople and the Holy Apostles in Thessalonike, were generally sponsored by the bureaucratic or ecclesiastical elite, often in conjunction with fresco decoration. The last major mosaic undertaking in the capital was at Hagia Sophia following the partial collapse of the dome in 1346. Shortly after 1355 the Pantokrator in the dome was restored, and images of John V Palaiologos, John the Baptist, and the Virgin were installed on the great eastern arch (Mango, Materials 66–76, 87–91). The mosaics on the eastern arch, covered by plaster for centuries, were rediscovered in 1989.

Cutler, Anthony. "Mosaic." In The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. : Oxford University Press, 1991.

Byzantine Fresco

A modified buon fresco, involving the application of lime-binding pigments directly to a layer of fine wet plaster added over an initial plaster coat, was used throughout Byz. times as an alternative to mosaic for wall decoration. No Byz. term corresponds exclusively to this technique. Because of its relative cheapness or its inherent modeling potential, fresco became increasingly popular in the 13th–14th C.

Examination of frescoes as well as literary allusions to painting indicate that pigments were applied in layers, even though the mixing of pigments in the modeling of flesh is found occasionally. Final flesh pigments, black or dark ochre outlines, and white highlights as well as inscriptions were normally added only after the initial layers of the painting had dried, a practice that has contributed to their loss. The range of color was limited to natural pigments that remained stable in conjunction with the lime of the plaster, for example, lime white and lime putty, ochres varying from bright red and yellow to dark brown, earth green, and carbon black. A black wash was commonly used under blue (azurite) or green to produce a dark ground. The appearance of more expensive pigments such as ultramarine blue (from lapis lazuli) and gold and silver foil distinguish lavish works. Vermilion is also not unusual, although it tends to turn black. The rich coloristic impression given by many surviving fresco programs is a testament to the ingenuity with which masters manipulated their limited palette.

Wharton, Annabel Jane. "Fresco Technique." In The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. : Oxford University Press, 1991.

Books on Mosaic and Fresco Decoration

-

-

Cyprus, Byzantine churches and monasteries : mosaics and frescoes

by

Call Number: NA3780 .H45 1998ISBN: 3929255154

Cyprus, Byzantine churches and monasteries : mosaics and frescoes

by

Call Number: NA3780 .H45 1998ISBN: 3929255154 -

The mosaics of Nea Moni on Chios

by

Call Number: NA3780 .M681 1985

The mosaics of Nea Moni on Chios

by

Call Number: NA3780 .M681 1985 -

Byzantine mosaic work : notes on history, technique & colour

by

Call Number: NA3780 .W55 2005ISBN: 9963642179

Byzantine mosaic work : notes on history, technique & colour

by

Call Number: NA3780 .W55 2005ISBN: 9963642179 -

Byzantine mosaic decoration : aspects of monumental art in Byzantium

by

Call Number: NA3780 .D39 1947

Byzantine mosaic decoration : aspects of monumental art in Byzantium

by

Call Number: NA3780 .D39 1947 -

Justinianic Mosaics of Hagia Sophia and Their Aftermath by

Call Number: NA3780 .T477 2017ISBN: 9780884024231Publication Date: 2017-10-16 -

Chora : the scroll of heaven by

Call Number: NA5870.K3 M36 2000 -

-

Byzantine painting : historical and critical study

by

Call Number: ND142 .G73 1979

Byzantine painting : historical and critical study

by

Call Number: ND142 .G73 1979 -

The Mosaics and Frescoes of St. Mary Pammakaristos (Fethiye Camii) at Istanbul by

Call Number: NA3780 .B38 1978ISBN: 0884020754Publication Date: 1978-01-01 -

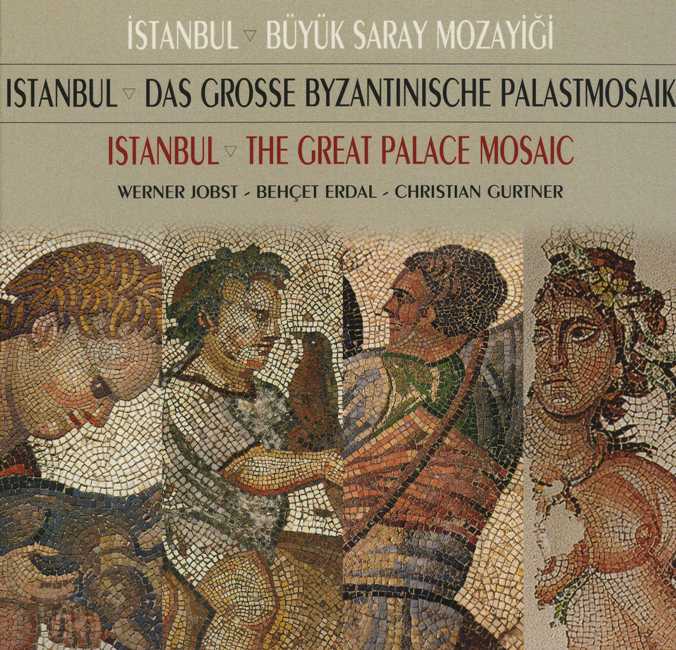

Istanbul Büyük Saray Mozayigi

by

Call Number: NA3792.B9 J63 1997ISBN: 9757538914Publication Date: 1998-12-31

Istanbul Büyük Saray Mozayigi

by

Call Number: NA3792.B9 J63 1997ISBN: 9757538914Publication Date: 1998-12-31 -

New Light on Old Glass by

Call Number: NK5108.8 .N49 2013ISBN: 9780861591794Publication Date: 2013-09-30 -

Örgülü Bizans döşeme mozaikler = interlaced byzantine mosaic pavements by

Call Number: NA3780 .D46 2002ISBN: 9759706814 -

The Great Palace : Mosaic Museum

by

Call Number: NA3780 .Y83 1987

The Great Palace : Mosaic Museum

by

Call Number: NA3780 .Y83 1987 -

Byzantine frescoes from Yugoslav churches

by

Call Number: ND2809 .R5 1963a

Byzantine frescoes from Yugoslav churches

by

Call Number: ND2809 .R5 1963a -

Mosaics of Thessaloniki by

Call Number: NA3780 .M66 2012ISBN: 9789606878367Publication Date: 2012-07-15 -

Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul by

Call Number: NA3780 .T48 1998ISBN: 0884022641Publication Date: 1998-01-01