Everyday Life in Constantinople

Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard: Workers on the field (down) and pay time (up), Byzantine Gospel of 11th century, Byzantine gospel. Paris, National Library,Cod. gr. 74.

Everyday Life

In the broad sense, encompasses the entirety of Byz. culture: thus, T. Talbot Rice's book (infra) includes sections on the imperial court, church, administration, army, etc. In the narrow sense, everyday life is ordinary human activity and comprises diet and costume, behavior and superstitions, entertainment, housing, and furniture. The subject is poorly studied and sources are limited: historiography, rhetoric, and liturgical texts are not very helpful, although they are the best known writings; archaeology provides some scattered data; hagiography, documents, and letters offer only small nuggets of information (P. Magdalino, BS 48 [1987] 28–38). The content of mural and book illustration is of mixed evidential value: the costumes, gestures, and attitudes of protagonists in sacred iconography appear to be conventional and often antique, yet peripheral details in both urban and rural scenes may well reflect current circumstances.

While daily life in late antiquity was municipally oriented and situated primarily in open spaces, Byz. funneled its energy inside closed buildings. A comparison of two great vitae, those of Symeon of Emesa (6th C.) and Basil the Younger (10th C.), reveals the change: Symeon is depicted in the streets and squares, Basil within the houses of his supporters. Public life did not totally disappear—some processions and feasts continued to be held in public—but it was significantly contracted: the theater ceased to exist, religious services dispensed with many outdoor liturgical ceremonies, even races and circus games tended to be replaced by Carnivals and by sports and competitions, such as polo and tournaments, which were on a reduced scale and socially restricted. The shift from reading aloud to silent reading, the adoption of silent prayer, the abandonment of public repentance, the playing of quiet Board Games like chess—all these belong to the same phenomenon of “privatization” of everyday life.

With the exception of churches, there was no new construction of public buildings in Byz. towns, and the regular city planning of antiquity, with squares, porticoes, and wide avenues, was replaced by a chaotic maze of narrow streets and individual habitats. The Houses of the nobility (villas or mansions) also lost their orderly arrangement, which was replaced by a group of irregularly shaped rooms, bedchambers, terraces, and workshops; also abandoned was their openness to nature in the form of the atrium—with its impluvium, inner garden, and fountain—or naturalistic floor mosaics. Houses became darker, and the shift in lighting from lamps to candles after the 7th C. contributed as well to this change.

The increased use of tables and of the writing desk influenced various habits—from reading and writing (including the format of the book) to dining and games. The bed as the symbol of the most private aspect of daily life became consistently distinct from chairs or stools, which were used for more social occasions. Pottery (see Ceramics) grew more uniform and less decorated than in antiquity; it served primarily the private needs of the family, whereas imperial Banquets used gold and silver ware.

A respect for the human body determined the form of ancient costume: the body was covered only minimally and there was no fear of nakedness. Byz. costume, however, which began to adopt the use of trousers and sleeves, was a reaction against the openness of antiquity, and heavy cloaks provided people with additional means of concealment.

Patterns of food consumption evidently changed as well: in the ordinary diet, the role of bread decreased, whereas meat, fish, and cheese became more important. Dining habits changed, too, from a relaxed reclining to the more formal sitting on chairs. While we can surmise that the actual diet was not spare by medieval standards, the predominantly monastic ideology of the Byz. condemned heavy meals and praised ascetic abstemiousness.

Bathing habits also changed: the public baths, which had served virtually as a club for well-to-do Romans, almost disappeared and ancient bath-houses were often transformed into churches. Provincial baths were few, located in log huts full of smoke coming from an open hearth.

The nuclear family was the crucial social unit responsible for the production of goods, so that hired workers (misthioi) and even slaves (see Slavery) were considered an extension of the family; the education of children was also the family's responsibility. The family was limited to a certain extent by the neighborhood, guild, or village community; it was these microstructures that took charge of organizing feasts. Women, who indisputably played a decisive role in the household, were compelled to remain in a special part of the house and to wear “decent” dress, which served clearly to distinguish a matron from the prostitute, whose more revealing costume suggested immoral conduct. The unity of the family was emphasized by the custom of common meals and by the father's right to indoctrinate (sometimes with physical force) all the members of his small household.

Depictions of everyday life are rare as primary subjects in art, although many indications can be gleaned from biblical images in MSS such as the Octateuchs where, for example, scenes of birth, legal penalties, and activities such as threshing and various modes of transportation reflect Byz. practice. A market scene appears in a fresco at the Blachernai monastery in Arta which depicts a procession of the Virgin Hodegetria. It shows merchants displaying their merchandise in baskets and on benches, fruit and beverage vendors, and their customers. By contrast, ceramic household vessels made for everyday use, when they do contain figural decoration of any sort, show scenes from mythology, fable, or epic.Alexander Kazhdan, Anthony Cutler

Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.oxfordreference

Geoponika by

Call Number: S429 .G413 2011ISBN: 9781903018699Publication Date: 2011-10-02It was a gathering together of many classical and post-classical agricultural works, from Pliny in ancient Rome to the 7th-century Cassianus Bassus and the 4th-century Vindonius Anatolius. Many of these no longer survive, making the Geoponika the more valuable. It is a source both for ancient Roman agricultural practice in the West, and for understanding Near Eastern agriculture and what went on in Byzantine Anatolia. It was once translated into English, in the early 19th century, but has usually only been accessible to scholars of Greek. The history of the manuscript is extremely complicated.The Byzantine Economy by

Call Number: HC294 .L34 2007ISBN: 9780521615020Publication Date: 2007-09-20This is a concise survey of the economy of the Byzantine Empire from the fourth century AD to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Organised chronologically, the book addresses key themes such as demography, agriculture, manufacturing and the urban economy, trade, monetary developments, and the role of the state and ideology. It provides a comprehensive overview of the economy with an emphasis on the economic actions of the state and the productive role of the city and non-economic actors, such as landlords, artisans and money-changers. The final chapter compares the Byzantine economy with the economies of western Europe and concludes that the Byzantine economy was one of the most successful examples of a mixed economy in the pre-industrial world. This is the only concise general history of the Byzantine economy and will be essential reading for students of economic history, Byzantine history and medieval history more generally. The Economic History of Byzantium by Call Number: HC294 .E25 2002ISBN: 0884022889Publication Date: 2002-01-01The longevity of the Byzantine state was due largely to the existence of variegated and articulated economic systems. This three-volume study examines the structures and dynamics of the economy and the factors that contributed to its development over time. The first volume addresses the environment, resources, communications, and production techniques. The second volume examines the urban economy; presents case studies of a number of places, including Sardis, Pergamon, Thebes, Athens, and Corinth; and discusses exchange, trade, and market forces. The third volume treats the themes of economic institutions and the state and general traits of the Byzantine economy. This global study of one of the most successful medieval economies will interest historians, economic historians, archaeologists, and art historians, as well as those interested in the Byzantine Empire and the medieval Mediterranean world.

The Economic History of Byzantium by Call Number: HC294 .E25 2002ISBN: 0884022889Publication Date: 2002-01-01The longevity of the Byzantine state was due largely to the existence of variegated and articulated economic systems. This three-volume study examines the structures and dynamics of the economy and the factors that contributed to its development over time. The first volume addresses the environment, resources, communications, and production techniques. The second volume examines the urban economy; presents case studies of a number of places, including Sardis, Pergamon, Thebes, Athens, and Corinth; and discusses exchange, trade, and market forces. The third volume treats the themes of economic institutions and the state and general traits of the Byzantine economy. This global study of one of the most successful medieval economies will interest historians, economic historians, archaeologists, and art historians, as well as those interested in the Byzantine Empire and the medieval Mediterranean world.Eat, Drink, and Be Merry (Luke 12:19) by

Call Number: TX360.B97 S67 2003ISBN: 9780754661191Publication Date: 2007-12-28This volume brings together a group of scholars to consider the rituals of eating together in the Byzantine world, the material culture of Byzantine food and wine consumption, and the transport and exchange of agricultural products. The contributors present food in nearly every conceivable guise, ranging from its rhetorical uses - food as a metaphor for redemption; food as politics; eating as a vice, abstinence as a virtue - to more practical applications such as the preparation of food, processing it, preserving it, and selling it abroad. We learn how the Byzantines viewed their diet, and how others - including, surprisingly, the Chinese - viewed it. Some consider the protocols of eating in a monastery, of dining in the palace, or of roughing it on a picnic or military campaign; others examine what serving dishes and utensils were in use in the dining room and how this changed over time. Throughout, the terminology of eating - and especially some of the more problematic terms - is explored. The chapters expand on papers presented at the 37th Annual Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, held at the University of Birmingham under the auspices of the Society for the Promotion of Byzantine Studies, in honour of Professor A.A.M. Bryer, a fitting tribute for the man who first told the world about Byzantine agricultural implements.Byzantine Constantinople by

Call Number: DR729 .B99 2001ISBN: 9004116257Publication Date: 2001-08-22This volume deals with the history, topography and monuments of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire and one of the greatest urban centers ever known, throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. It contains 21 papers that emanate from an international workshop which was held at Istanbul in 1999. Divided into eight sections, the collection addresses a variety of interconnected topics, ranging from topography to ritual and ideology, archaeology, religious and secular architecture, patronage, commercial life, social organization, women's roles, communities, urban development and planning. Partly drawing on new archaeological and textual evidence, partly directing new questions to or reinterpreting previously available sources, the papers presented here fill important gaps in our knowledge of Constantinople and enhance our conception of the city as both a physical and social entity.Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire by

Call Number: DF521 .R37 2006ISBN: 0313324379Publication Date: 2006-03-30Discover how ordinary people lived during the Middle Ages in the eastern Mediterranean in this unparalleled exploration of life in the Byzantine Empire. Learn how the subjects of the Byzantine Empire kept track of time with sundials and water clocks. Witness a typical wedding and all of the traditions followed by the bride, groom, and guests. Find out how the Byzantines kept up their appearance, covering everything from skincare to dental care. Learn the rules of games that children played, and explore everything in the city of Constantinople, from tourist attractions to city administration and defense strategies. Learn about sports entertainment at the Hippodrome as well as theaters and other festivals. Compare city life to that of the country, military, and monastery. Understand Byzantine humor, education system, and musical instruments. Ideal for high school students and undergraduates. Even general readers can explore the world of the Byzantine Empire in this comprehensive study that covers everything from clothing styles to typical city life.Rautman discusses not only general issues of everyday life in the Byzantine Empire, but also probes into very specific topics. Questions such as Who were some writers during the Byzantine Empire? as well as, How did people brush their teeth? are answered in this extensive study. Topics include Byzantine worldviews, how their society and economy flourished, and how families were structured. Rautman also looks at the city of Constantinople (modern Istanbul), as well as other cities and towns and the countryside. Other topics include life in the military and monastery, artistic life, and education beliefs. Also included are a list of Byzantine rulers, a list of Byzantine and contemporaneous writers, and a glossary. This all-inclusive study is essential to all high school, academic, and public library reference shelves.Feast, Fast or Famine by

Call Number: DF521 .F43 2005ISBN: 1876503181Publication Date: 2017-06-22In recent decades there has been an increasing interest in the study of food and drink in the ancient, Mediaeval and Byzantine worlds and of their supply and consumption. This volume presents selected papers from the biennial conference of the Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, which was held at the University of Adelaide, 11-12 July 2003. The theme was food and drink in Byzantium. Published selectively in the present volume, the papers of the conference are augmented by contributions from international scholars. While some papers address the use of food directly (children’s diet, fasting) or tangentially (in love spells), or discuss philosophical approaches towards food (vegetarianism), other papers in this volume examine the topic from another perspective: the role and perception of food and drink – and their consumption – in society. Yet others examine issues of supply (military logistics) and the role it played in shaping Byzantium. This volume will appeal to readers interested in the history of food, in late antique and Byzantine society, in Byzantine rhetoric, in magic in late antiquity and in the Jews in early Byzantium. Trade in Byzantium : papers from the third international Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium, İstanbul 24-27 June, 2013 by Call Number: HF405 .I58 2016ISBN: 6059388051Publication Date: 2016In the ByzantineEmpire, Constantinople served not only as an administrative, military, and religiouscenter, but also as one of trade and commerce. The city wasselected as the new imperial capital due to its geographical advantages, its vasthinterland, its situation as an ideal vantage point for travel by land and sea, and its safe natural harbors, making it a perfect location for trade. Considering that medieval Anatolia, and especially Constantinople, was located at thecenter of a broadtrade network and was a center of both production and consumption, trade is rightfully a continuing subjectmatter of Byzantine studies. Inaddition, since 2004, the Directorate of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums has carriedout archaeological research in Üsküdar, Sirkeci, and Yenikapi, as part of the Marmaray and Metro projects. The excavation shaverevealedspectaculararti fact sand new knowledge on Byzantinetrade, ship-building technology, and ship sand their cargo. In light of harbor excavationre sultsand information accumulated from other on going research, it was the right time to re-evaluatetrade in Byzantium. New finding sand knowledge arising from the Yenikapi excavations, in particular, gave reasontore visit issues of trade in Byzantium again. The articles collected in this volume derive from papers presented at the Third International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium on "Trade in Byzantium" held in Istanbul on 24-27 June 2013.

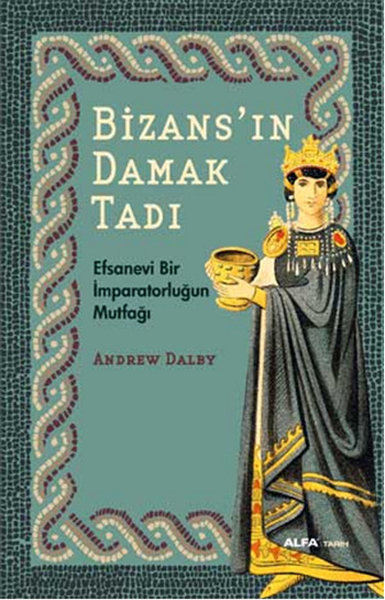

Trade in Byzantium : papers from the third international Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium, İstanbul 24-27 June, 2013 by Call Number: HF405 .I58 2016ISBN: 6059388051Publication Date: 2016In the ByzantineEmpire, Constantinople served not only as an administrative, military, and religiouscenter, but also as one of trade and commerce. The city wasselected as the new imperial capital due to its geographical advantages, its vasthinterland, its situation as an ideal vantage point for travel by land and sea, and its safe natural harbors, making it a perfect location for trade. Considering that medieval Anatolia, and especially Constantinople, was located at thecenter of a broadtrade network and was a center of both production and consumption, trade is rightfully a continuing subjectmatter of Byzantine studies. Inaddition, since 2004, the Directorate of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums has carriedout archaeological research in Üsküdar, Sirkeci, and Yenikapi, as part of the Marmaray and Metro projects. The excavation shaverevealedspectaculararti fact sand new knowledge on Byzantinetrade, ship-building technology, and ship sand their cargo. In light of harbor excavationre sultsand information accumulated from other on going research, it was the right time to re-evaluatetrade in Byzantium. New finding sand knowledge arising from the Yenikapi excavations, in particular, gave reasontore visit issues of trade in Byzantium again. The articles collected in this volume derive from papers presented at the Third International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium on "Trade in Byzantium" held in Istanbul on 24-27 June 2013. Bizans'ın damak tadı : kokular, şaraplar, yemekler by Call Number: TX725.B97 D3520 2004Publication Date: 2004Bizans İmparatoru I. Manuel Komnenos bir gün sarayına dönerken seyyar tezgâhında meze satan bir kadının yanından geçti. Ansızın sıcak çorbadan içip lahanadan da bir lokma yemeyi çekti canı. Hizmetkârlarından Anzas, açlıklarına gem vurmanın daha iyi olacağını söyledi: Saraya vardıklarında bol, doğru dürüst yiyecek olacaktı. Ona sert sert bakan Manuel, canı ne çekerse onu yapacağını söyledi. Dosdoğru satıcı kadının elindeki, sevdiği çorbayla dolu kâseye doğru ilerledi. Eğildi, çorbayı açgözlülükle içti, ayrıca bol bol da sebze yedi. Sonra cebinden bronz bir stater çıkarttı ve adamlarından birine uzattı. "Bunu bozdur," dedi. "Hanıma iki oboloi ver, diğer ikisini de bana iade etmeyi unutma!" Bizans mutfağı baharat aşkı ile deniz ürünlerinin senteziydi. Büyük Constantinus'un kurduğu şehirde yaşayanlar kuzu etine ilk kez biberiye kattılar, mutfaklarından safranı eksik etmediler, pastırmayı seve seve yediler, havyarı pek makbul saydılar. Portakal ve patlıcan onlar sayesinde yerli ürün haline geldi. Andrew Dalby, özgün Bizans kroniklerini kullanarak yazdığı bu öncü çalışmasında, Bizans mutfağının incelmişliğini ve bu toprakları istila eden Haçlıları şaşkına çeviren sebze ve meyve çeşitlerini sunuyor. Kitapta tatlı tatlı anlatılan Bizans sokaklarının kargaşası, sokak satıcıları, yemek kokuları, bugünkü İstanbul'un renklerini hatırlatıyor insana. Dalby'nin satırlarında kokulu şarapları, bin bir balık tarifini, şifalı otları, zeytin çeşitlerini, enginarı, mercimeği ve daha birçok lezzeti bulacaksınız.

Bizans'ın damak tadı : kokular, şaraplar, yemekler by Call Number: TX725.B97 D3520 2004Publication Date: 2004Bizans İmparatoru I. Manuel Komnenos bir gün sarayına dönerken seyyar tezgâhında meze satan bir kadının yanından geçti. Ansızın sıcak çorbadan içip lahanadan da bir lokma yemeyi çekti canı. Hizmetkârlarından Anzas, açlıklarına gem vurmanın daha iyi olacağını söyledi: Saraya vardıklarında bol, doğru dürüst yiyecek olacaktı. Ona sert sert bakan Manuel, canı ne çekerse onu yapacağını söyledi. Dosdoğru satıcı kadının elindeki, sevdiği çorbayla dolu kâseye doğru ilerledi. Eğildi, çorbayı açgözlülükle içti, ayrıca bol bol da sebze yedi. Sonra cebinden bronz bir stater çıkarttı ve adamlarından birine uzattı. "Bunu bozdur," dedi. "Hanıma iki oboloi ver, diğer ikisini de bana iade etmeyi unutma!" Bizans mutfağı baharat aşkı ile deniz ürünlerinin senteziydi. Büyük Constantinus'un kurduğu şehirde yaşayanlar kuzu etine ilk kez biberiye kattılar, mutfaklarından safranı eksik etmediler, pastırmayı seve seve yediler, havyarı pek makbul saydılar. Portakal ve patlıcan onlar sayesinde yerli ürün haline geldi. Andrew Dalby, özgün Bizans kroniklerini kullanarak yazdığı bu öncü çalışmasında, Bizans mutfağının incelmişliğini ve bu toprakları istila eden Haçlıları şaşkına çeviren sebze ve meyve çeşitlerini sunuyor. Kitapta tatlı tatlı anlatılan Bizans sokaklarının kargaşası, sokak satıcıları, yemek kokuları, bugünkü İstanbul'un renklerini hatırlatıyor insana. Dalby'nin satırlarında kokulu şarapları, bin bir balık tarifini, şifalı otları, zeytin çeşitlerini, enginarı, mercimeği ve daha birçok lezzeti bulacaksınız.Byzantine Women by

Call Number: HQ1147.B98 B98 2006ISBN: 9780754657378Publication Date: 2006-09-28This volume brings together a group of international scholars, who explore many unusual aspects of the world of Byzantine women in the period 800-1200. The specific aim of this collection is to investigate the participation of women - non-imperial women in particular - in supposedly 'masculine' fields of operation. This new research across a range of disciplines attempts to provide an analysis of the activities of and attitudes towards Byzantine women in this period. Using evidence from sources as diverse as tax registers, monastic foundation documents, twelfth-century novels, historical texts, art history and the writings of women themselves, such as the hymnographer Kassia and the historian Anna Komnene, these papers elucidate the context in which Byzantine women lived. They emphasize the variety of female experiences, the circumstances that shaped women's lives, and the ways in which individual women were perceived by their society. Contributions focus on women's dress, their participation in the street life of Constantinople, their appearance in Byzantine fiscal documents, their monastic foundations, their engagement with entertainment at the imperial court, and the way heroines are portrayed in the Byzantine novels. Analysis of the writings of the hymnographer Kassia, the networking of Mary 'of Alania' and the ways she overcame the disadvantages of being a foreign-born empress, and the family values reflected in Anna Komnene's Alexiad, draw attention to specific problems. All these aim to expand our understanding of the circumstances that shaped women's lives and expectations in the Middle Byzantine period and to analyze the range of women's experiences, the roles they played and the impact they made on society.Women, Family and Society in Byzantium by

Call Number: HQ1147.B98 L35 2011ISBN: 9781409432043Publication Date: 2011-08-28Angeliki Laiou (1941-2008), one of the leading Byzantinists of her generation, broke new ground in the study of the social and economic history of the Byzantine Empire. Women, Family and Society in Byzantium, the first of three volumes to be published posthumously in the Variorum Collected Studies Series, brings together eight articles published between 1993 and 2009. Demonstrating Professor Laiou's characteristic attention to the relationship between ideology and social practice, the first five articles concern the status of women as evidenced through legal, narrative, hagiographical, and archival sources, while the final three investigate conceptions of law and justice, the vocabulary and typology of peasant rebellions, and the and the form and evolution of political agreements in Byzantine society. Gemüse in Byzanz : die Versorgung Konstantinopels mit Frischgemüse im Lichte der Geoponika by Call Number: DR729 .K63 1993ISBN: 3900538417Publication Date: 1993Gemüse aller Art zählen seit jeher zu den wichtigsten Nahrungsmitteln des Menschen. Die ganzjährige Versorgung einer Großstadt mit frischem Gemüse stellt heute normalerweise kein Problem dar. Doch wie gestaltet sich eine ausgewogene und umfassende Versorgung mit Nahrungsmitteln für die Metropolen der Spätantike und des Mittelalters, zu Zeiten vorindustrieller Bedingungen von Produktion, Transport und Verteilung also? In der vorliegenden Untersuchung erarbeitet Johannes Koder auf der Basis byzantinischer und mittelalterlicher Quellen und der topopgraphischen Situation deas Fallbeispiel Konstantinopel, der Kaiserresidenz und Weltstadt am Bosporus, mit mehreren hunderttausend Einwohnern im 6. Jahrhundert. Dabei geht es um: Anbauflächen und Gemüsearten wann der Markt über welche Gemüse verfügte wie das Produkt zum Konsumenten kam und auf welche Art er es zubereitete.

Gemüse in Byzanz : die Versorgung Konstantinopels mit Frischgemüse im Lichte der Geoponika by Call Number: DR729 .K63 1993ISBN: 3900538417Publication Date: 1993Gemüse aller Art zählen seit jeher zu den wichtigsten Nahrungsmitteln des Menschen. Die ganzjährige Versorgung einer Großstadt mit frischem Gemüse stellt heute normalerweise kein Problem dar. Doch wie gestaltet sich eine ausgewogene und umfassende Versorgung mit Nahrungsmitteln für die Metropolen der Spätantike und des Mittelalters, zu Zeiten vorindustrieller Bedingungen von Produktion, Transport und Verteilung also? In der vorliegenden Untersuchung erarbeitet Johannes Koder auf der Basis byzantinischer und mittelalterlicher Quellen und der topopgraphischen Situation deas Fallbeispiel Konstantinopel, der Kaiserresidenz und Weltstadt am Bosporus, mit mehreren hunderttausend Einwohnern im 6. Jahrhundert. Dabei geht es um: Anbauflächen und Gemüsearten wann der Markt über welche Gemüse verfügte wie das Produkt zum Konsumenten kam und auf welche Art er es zubereitete.A Byzantine Encyclopaedia of Horse Medicine by

Call Number: SF951 .M477 2007ISBN: 9780199277551Publication Date: 2007-06-21The veterinary compilation known as the Hippiatrica is a rich and little-known source of information about the care and medical treatment of horses, donkeys, and mules in late antiquity and the Byzantine period. This book provides a guide both to its intriguing contents, and to its complex textual history. - ;How were Greek texts on the care and medical treatment of the horse transmitted from antiquity to the present day? Using the evidence of Byzantine manuscripts of the veterinary compilation known as the Hippiatrica, Anne McCabe traces the journey of the texts from the stables to the medieval scriptorium and ultimately to the printed edition.Everyday Life in Byzantium by

Call Number: DF531 .R5 1987ISBN: 0880291451Publication Date: 1987-12-01The book covers foundation and growth of the capital, the daily ritual of the imperial court and the church. Everyday life in Byzantium by Call Number: DF520 .K38 2002ISBN: 9602145315Publication Date: 2002A magnificent huge illustrated volume, describing in detail the daily life in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Everyday life in Byzantium by Call Number: DF520 .K38 2002ISBN: 9602145315Publication Date: 2002A magnificent huge illustrated volume, describing in detail the daily life in the Eastern Roman Empire.