Byzantine Art

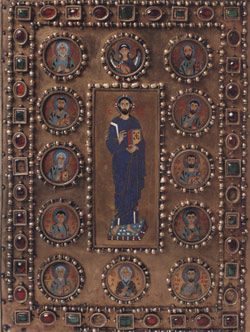

1-Art, The M. M. O. "Byzantine Book Cover with Icon." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified June 21, 2018. https://www.ancient.eu/image/8960/.

2-Team, Hagia S. R. "The Virgin and Child Mosaic, Hagia Sophia." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified January 24, 2018. https://www.ancient.eu/image/7973/.

(τέχνη). The Greek term techne had a broad range of meanings, including mental dexterity, linguistic ability, and trickery as well as the skills of rulers and physicians. It therefore implied something closer to craft and denied a privileged role to the work of art and to its creator. Art was understood not as completing nature, as in Aristotle, nor as possessing value independent of nature, as in the modern view, but as nature: art reproduced reality, including those aspects of it that were normally invisible (John of Damascus, ed. Kotter, Schriften 3:126.2–3). Despite centuries of theorizing about the relationship of the image to its prototype, not until the 15th C. (Manuel Chrysoloras) was a practical distinction drawn between the image and that which it represented. Equally, written accounts of works of art rarely distinguish the material of which they were made: differentiations between the principal genres and materials are usually to be found only in inventories where they served quite other purposes than aesthetic appreciation or even evaluation as stimuli to religious faith. But descriptions of mosaic and wall painting (see Monumental Painting), the two main types of monumental decoration in Byz., largely ignore the contribution of the medium to the work's final effect, emphasizing instead the lifelike quality of the image and its impact upon the beholder. Where the medium can be discerned at all, reports on icons, ecclesiastical silver, enamels, and textiles—some of the most frequently noted categories of portable works—stress function rather than form, message rather than materials.

Literature provides our primary means of access to the Byz. response to that which we call art and confirms the view that the purposes of representational art took precedence over its nature and materials. The effects of art—the magnificence of a building and its decoration, the glittering splendor of a piece of metalwork—all but efface other considerations. The purpose of architecture is to magnify the builder and often, as described in the Vita Basilii, to show that he has recovered the glory of the past. Such an approach links imperial founders, ktetors of lesser rank, and church builders. The significant aspect of a structure lies in what it says about its patron: it shows that an emperor has restored (often “from the ground up”) what had crumbled, be it the fabric of a building, the reputation of a city, or the strength of right belief.

On the one hand, what was ancient, when it survived, was prized for its own sake; on the other, its restoration was a Christian's duty and a credit to him. Since an icon was understood to function by virtue of perfect correspondence to its subject, panels were frequently “made anew” (Skyl. 384.21–24) and portraits in mosaics and MSS often remade. Lacking autonomous value as art, frescoes were overpainted with subjects sometimes quite different from the originals. Nonetheless, both the means by which pictures were produced and their iconography demonstrate the respect for authority and tradition (Mansi 13:252C) and the emphasis on orthodoxy of thought and behavior, apparent in other aspects of Byz. culture. Many works can be shown to have a more or less close dependence upon earlier examples, due in some cases to direct derivation but more often to the employment of a conventional and ubiquitous visual vocabulary. This lexicon included individual figures and poses, gestures and backgrounds preserved either in model-books (see Models and Model-Books) or, more likely, in the memory of craftsmen. Such elements were used or modified, and their syntactical relationships adjusted, according to context.

Thoroughly pragmatic, artists borrowed established forms, much as builders used spolia, and usually invented only when an exemplar was not at hand. How faithfully older forms were transmitted depended upon opportunities for access to models and the purpose, training, and native ability of the artist. This approach to artistic production was reinforced by socially sanctioned notions of decorum, of what was appropriate to a particular type of commission. Although there were variations in the size of a ktetor's investment, church programs of decoration conformed to highly developed ideas of what was fitting. Works in other favored media, above all textiles, Book Illustration, and metalwork, display similar homogeneity. While the same genres characterized Islamic art, the latter exhibited neither the Byz. emphasis on sacred decoration nor the resultant body of canonical subject matter. The overriding Byz. concern with an established and limited iconographical corpus likewise distinguishes it from the medieval West: most of the “profane” subjects—the virtues and vices, the liberal arts, the representation of trades and crafts—are largely missing from Byz. art.

The exploitation of older models was a phenomenon common to the visual arts and literature. Just as the 10th-C. historian Leo the Deacon was content to use descriptions of battles taken from Agathias writing four centuries earlier, so the 14th-C. mosaics of the Chora monastery, for example, quote details from the 10th-C. Joshua Roll. Such “antiques” were valued both for their age and their potential as models. As descriptions were interchangeable in texts, so were details of physiognomy, clothing, and setting in art: identity often depended as much on inscriptions as on formal variation. The benign and constant cannibalism of earlier work largely undercuts the notion of successive renaissances that have been imposed on particular periods. The supposition that painters of the 6th, 10th, and early 14th C. were more interested in antiquity than those of other times attributes to them an unusual motivation when, in fact, the use of ancient types was a form of economy on their part. The more frequent appearance of “classicizing” elements in certain eras is merely because of the fact that these were periods of cultural revival producing more works of high quality.

While particular instances of copying may reflect an act of choice on the part of a patron, this attitude was culturally determined. Overt examples of the political supervision of artistic production are few, but social control was compelling and depended on the various functions assigned to the work of art. Basil the Great (PG 32:229A) regarded images, like the lives of saints, as inspirations to virtue. More concretely, for Gregory of Nyssa (PG 46:737D) they had the value of “silent writing.” This didactic role was expanded in the 8th and 9th C. For the patriarch Nikephoros I the educative power of icons exceeded that of words, while Photios saw representations of martyrdom as more vivid than writing (L. Brubaker, Word and Image 5 [1989] 23f). Independent of such theoretical statements, art provided a vehicle for the expression of supplications and gratitude to God (Sophronios, PG 87.3:3388C). Icons were a means of access to the divine and responsible, Psellos's mother believed (An.Komn. 2:34.8–10), for human success. As materially rich creations, works of art were considered proper gifts at holy sites (Piacenza pilgrim) and, as the will of Eustathios Boilas and the diataxis of Michael Attaleiates make clear, to churches and monasteries.

Other types of document, notably the ekphrasis, emphasize the presence of Christ, his mother, and his saints, in their images. This sort of “realism” differs from that which allowed actuality to obtrude into representations of agriculture, navigation, and the like, and to invest biblical and hagiographical events with details that the artist's contemporaries could recognize. Since all attention was paid to the immediate significance of a scene, no attempt was made to present the past as such (see History Painting). Constantine I, for instance, was sometimes given the features of the reigning monarch, and incidents of the Old Testament were employed for their value as prefigurations of current events.

Despite such constants, developments in both style and subject matter are evident over the centuries, particularly in monumental painting, which, to a much greater extent than in the West, was the dominant visual medium. Such changes are in part to be explained by church doctrine: the Second Council of Nicaea had defined the manner of representation as the domain of the artist. Before this time, art displayed the iconographical and formal diversity characteristic of late antiquity and its far-flung cities. Lively scenes drawing on the everyday world distinguish both imperial imagery (Barberini ivory) and Christian themes (Rossano Gospels). A more rigorous definition of acceptable subject matter and its modes of presentation emerged from the search for authoritative, ancient statements concerning the validity of images both before and during Iconoclasm. To a degree this debate was responsible for the evolution of an attitude, akin to encyclopedism, toward the artistic heritage that was at once selective and prescriptive. In the service of dogmatic clarity, art of the 10th and early 11th C. exhibits a formal austerity based on the principles of frontality and symmetry.

These features have been seen as reducing the monumentality attributed to the painting of the “Macedonian Renaissance” but they are symptoms not causes. Rather, the late 11th- and 12th-C. desire to express more complex Christological ideas and more affective expressions of emotion widened the range of art, in the creation of which the number of identifiable and named artists increased greatly. But territorial losses and the fall of Constantinople to the Latins in 1204 brought to a close four centuries in which the artistic hegemony of the capital had been recognized and emulated beyond the confines of the empire. Already in the 12th C. both Latin and Turkic elements can be found in Byz. art; this trickle became a spate in and after the late 13th C. Even before the Civil War of 1341–47 cut short a brief Palaiologan revival, the sponsorship of works of art had passed into the hands of local magnates, both lay and ecclesiastical; the final 150 years display a range of representational quality and manners at odds with the splendor and uniformity that had characterized 9th–12th-C. production and on which the reputation of Byz. art has long been based. Only very recently has the appropriateness of modern standards such as aesthetic autonomy and independence of its ideological well-springs been questioned (R. Nelson, Art History 12 [1989] 144–57). The recovery of and sympathy for the context in which this body of production came into being is now seen as a more direct route to the understanding of Byz. art.

Cutler, Anthony. "Art." In The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. : Oxford University Press, 1991.

Byzantine Architecture

Kariye (Chora) Museum Bigdaddy1204, . "Theodosian Walls." Ancient History Encyclopedia.

Byz. architecture constitutes a building tradition generally associated with the history of the late Roman and Byz. empires and, to an extent, with its wider sphere of influence over a period spanning from ca.300–ca.1450. Byz. architecture defies a comprehensive conventional definition on either cultural, geographical, chronological, or stylistic bases. Between the 4th C. and the 15th C. several more-or-less coherent architectural developments and interludes took place that can be roughly grouped into seven chronological periods.

First Period (4th to 5th C.)

Architecture during this period represents the perpetuation of tradition within the cultural framework of the Greco-Roman world and the political framework of the Roman Empire. This perpetuation of established architectural practice accounts for the degree of continuity in the regional traditions of planning, structural solutions, building technique, and decoration. Two factors play a decisive role in the architectural development of the period: urban survival and active christianization. Urban centers witnessed a slow but steady shift from pagan to Christian patronage of public buildings. Christian churches—predominantly basilicas—derived generically from pagan prototypes, and their construction was entrusted to established workshops that had previously been employed on imperial pagan projects. Large-scale building under imperial auspices was one of the major industries in the Roman world, and the movement of manpower and technical personnel (architects, surveyors, etc.) from one completed building project to another was standard practice. This, in fact, constituted the essence of what we refer to as “workshop practice.”Building types such as the martyrion, baptistery, and mausoleum were also constructed in large numbers. Martyriadisplay a considerable variety of plan types, reflecting the particular requirements of preexisting customs and functions accommodated on their sites. Mausoleums, large and small, which initially were freestanding and independent, increasingly become attached to church buildings as christianization proceeded.

Second Period (6th C.)

This was the period of greatest architectural productivity in Byz. history. Often identified with the policy of reconquest of Emp. Justinian I, the vast building program was, in fact, begun by his predecessors Anastasios I and Justin I and continued by his successor, Justin II. The success of this grand enterprise was facilitated by the survival of the imperial order within the framework of the fully christianized, urban society. In a comprehensive record of the building accomplishments of Justin I and Justinian I, Prokopios of Caesarea provides us with a catalog of buildings and relates many details about the realization of the imperial program. This meticulous account, which includes descriptions of whole new towns, forts, churches, palaces, public buildings, markets, cisterns, aqueducts, and so on, is substantially confirmed by preserved buildings and archaeological finds.Notwithstanding the survival of regional building practices, the period was characterized by the much more pronounced impact of the capital. Certain building types (basilican churches, mausoleums, cisterns) continued to be constructed according to the established norms of a given region. At the same time, architecture was now also “exported” from Constantinople, the center of imperial administration. Whether in the form of new church plan typessuch as the domed basilica, new structural solutions involving the use of vaulting, standardized building techniques, or the nature of architectural decoration, there is a strong indication of direct connections of the center with regional affairs. The Marble Trade and the shipping of building components (columns, capitals, and church furniture), illustrate the degree and the character of the impact of Constantinople. This phenomenon is to be understood in the light of extensive construction in frontier regions, often in newly conquered territories, with the aim of consolidating recently established borders.

Third Period (7th to mid-9th C.)

In striking contrast to the preceding building boom this period is characterized by a virtual absence of construction. Beleaguered by foreign wars and internal crises, the empire experienced profound changes. The decline of cities was manifested in the physical decay of their fabric. The very meaning of “construction” during this period was practically reduced to preservation, repair, and patchwork. New building other than fortifications was rare, and large-scale construction exceptional. The few surviving examples in the latter category reveal conservative traits and expedient dependence on spolia.

Fourth Period (mid-9th through 11th C.)

By the middle of the 9th C. relative political, religious, and cultural stability within the territorially shrunken Byz. Empire had been restored. Under the auspices of the Macedonian dynasty, building began anew, though under very different circumstances. Given new cultural parameters and an altered social structure, an architecture emerged that showed marked signs of departure from the old tradition. Palaces and palace halls of this period reveal a fresh source of influence—Islamic art and architecture (see Islamic Influence on Byzantine Art). Aspects of Islamic impact can also be seen in the decorative vocabulary of Byz. architecture, now significantly expanded beyond its traditional, classicizing framework.Church architecture also reveals other sources of external influence, for example, Armenia. Church types proliferated while undergoing considerable reductions in scale. The latter phenomenon has been viewed as the function of shrunken economic means and the reduced demand for space of a smaller population. Still, some fairly large churches, notably piered basilicas, continued to be built during this period. The frequent appearance of smaller, centralized, and domed churches, on the other hand, involved changes in the shape of the liturgy and altered symbolic perceptions of the church building. Seen as a miniature version of the cosmos, the church functioned symbolically regardless of its size. Demands for space in churches during this period were generally solved not by increasing the volume of the naos but by adding lateral spaces and parekklesia. When built simultaneously with the church itself, these parekklesia, unlike the earlier mausoleums, were often carefully integrated aspects of a building's overall form. Thus, for example, the multiplication of domes on churches of this period was the direct by-product of multiple chapels planned integrally with the main church.

Fifth Period (12th C.)

Notwithstanding the military setbacks and the resulting geopolitical changes that affected the empire during the last third of the 11th C., architectural activity in the Komnenian period displayed remarkable vitality, with Constantinople playing the role of central clearinghouse for architects, artisans, ideas, and materials. Formal characteristics, decorative features, and even structural techniques are shared by a very large number of buildings, many of which were built in the provinces and even beyond the frontiers of the empire. This phenomenon, which parallels a similar trend in Byz. painting, reflects an increasing mobility in the Mediterranean basin. Both can be related to a general increase in East-West cultural interaction.

Sixth Period (13th C.)

The period of the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–61) saw the disappearance of the capital's hitherto preeminent architectural influence. Instead, architecture flourished in several new centers of the splintered empire (Nicaea, Trebizond, Arta), each displaying distinctive local architectural characteristics. The stylistic coherence of the Komnenian epoch gave way to a new diversity. Thus, the political decentralization of the empire left its lasting imprint on the development of Byz. architecture.

Seventh Period (14th to 15th C.)

Following the Byz. recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the city once more became the premier center of architectural activity. In addition to the remodeling and expansion of existing buildings, a fair number of new churches, monastic buildings, and palaces were constructed, particularly during the last decade of the 13th C. and during the first two decades of the 14th C. Church architecture during this period perpetuated the tradition of smallscale construction. The major stylistic change came in the treatment of walls, which lost their tectonic qualities in favor of flat surfaces covered by decorative patterns. The same disregard for spatial-structural articulation also permeated interiors. Here flat wall surfaces carried several tiers of continuous horizontal bands of monumental paintingbroken up into numerous small individual scenes.The civil wars of the 1320s and 1340s brought architectural activity in the capital to a virtual end. Constantinopolitan architectural style was transplanted elsewhere (e.g., Mesembria, Skopje and vicinity, Bursa), presumably by migrant workshops, which found themselves employed by Bulgarian, Serbian, and Ottoman patrons. A few centers, such as Thessalonike and Mistra, kept the local architectural traditions alive beyond the early demise of Byz. architectural production in Constantinople. (See also Constantinople, Monuments of.)

Ćurčić, Slobodan. "Architecture." In The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. : Oxford University Press, 1991.